Recursive Language Models: Stop Stuffing the Context Window

The next big thing might be recursive language models (RLMs).

Recently, I saw a ton of interest on Recursive Language Models (RLMs) and thought it would be great to write about why this is an important paper.

This will be a longer one than usual, so feel free to bookmark it if you want to read it later. But I think it will be worth the time to understand what RLM is and the excitement around it.

At a high level, RLM introduces a deceptively simple idea that rethinks how language models interact with long documents. Instead of cramming text into the context window and hoping the model doesn’t lose track, RLMs treat text as an external environment that the model programs against.

I know what you are thinking, this sounds a lot like standard coding agents connected to tools or even a classical RAG system. But bear with me, it gets more interesting than that.

The bigger question is: how does an 8B parameter model using the proposed approach come close to GPT-5 on long-context tasks?

What’s happening here? Let’s break it down.

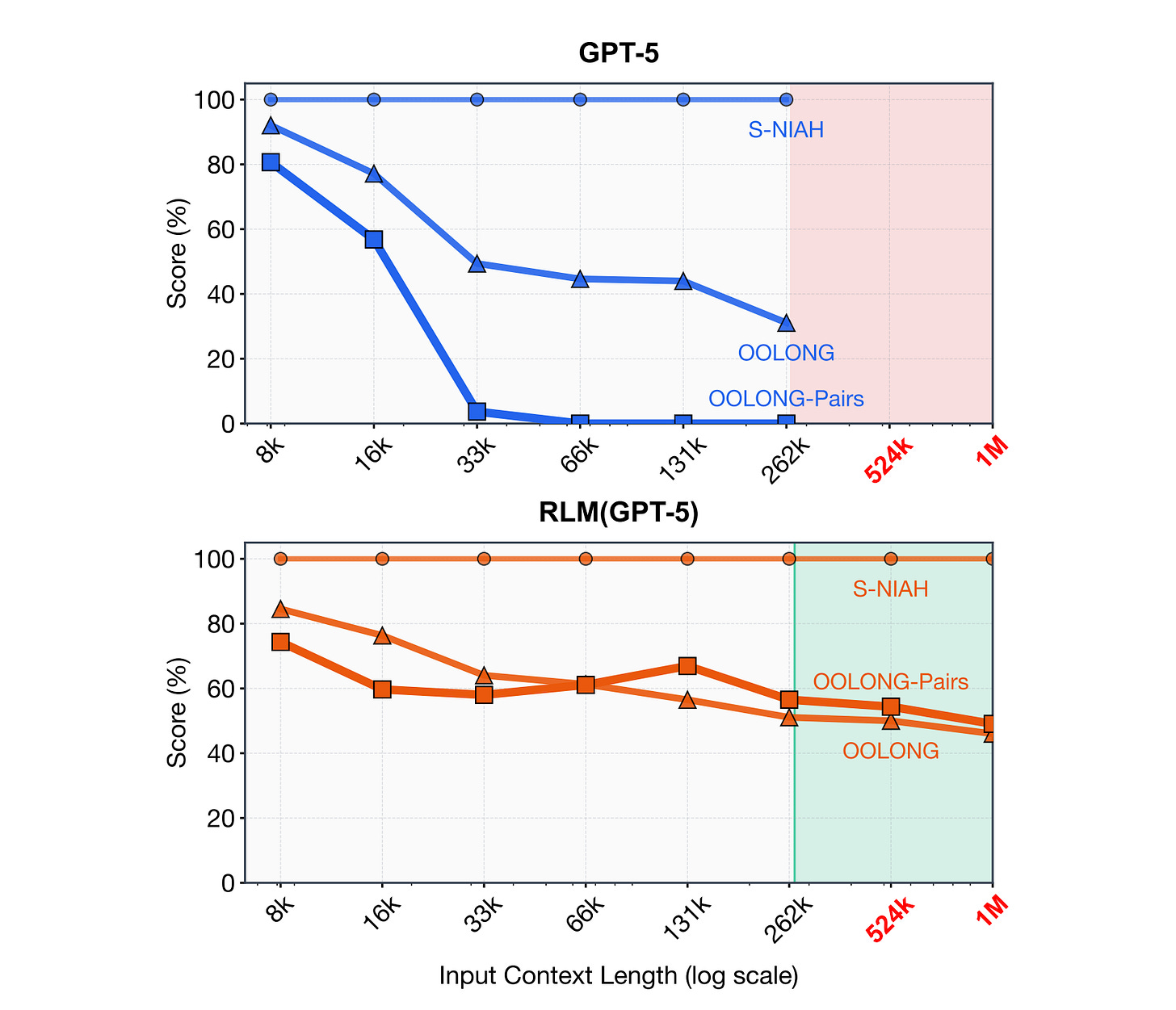

The Problem: Context Rot

We keep building bigger context windows: 128K, 1M, 10M tokens. But a larger window doesn’t solve the core issue where model performance degrades as context grows. Key details get buried. Reasoning quality drops. The authors refer to this as “context rot,” and anyone who has tried to get a model to reason over a long document has experienced it firsthand.

Current mitigations (RAG, summarization, chunking) all share the same assumption: the retrieved or compressed text must eventually become tokens in the prompt. The model has to “see” everything it reasons about.

RLMs challenge that assumption entirely. Here’s how.

The Model is a “Programmer”, Not a “Reader”

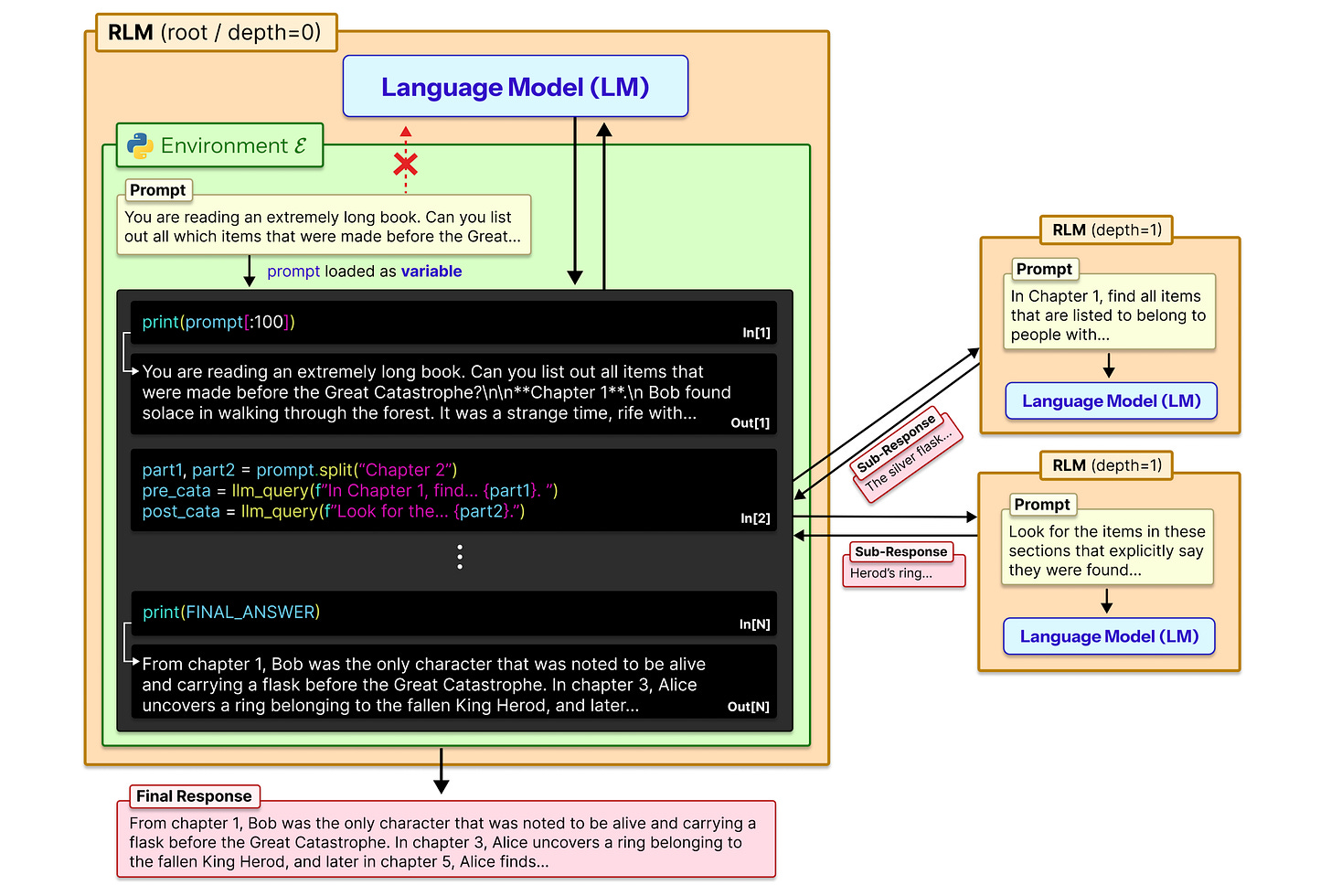

What if the model didn’t have to read the document at all? Instead of feeding a document into the model, RLMs place the document inside a coding environment (a Python REPL) and let the model write programs to interact with it. The model never ingests the raw text. It writes code (grep for a keyword, slice out a section, iterate over chapters), and only the results of that code enter the context window.

Think of it as the difference between reading a database and querying a database. Traditional LMs read. RLMs query.

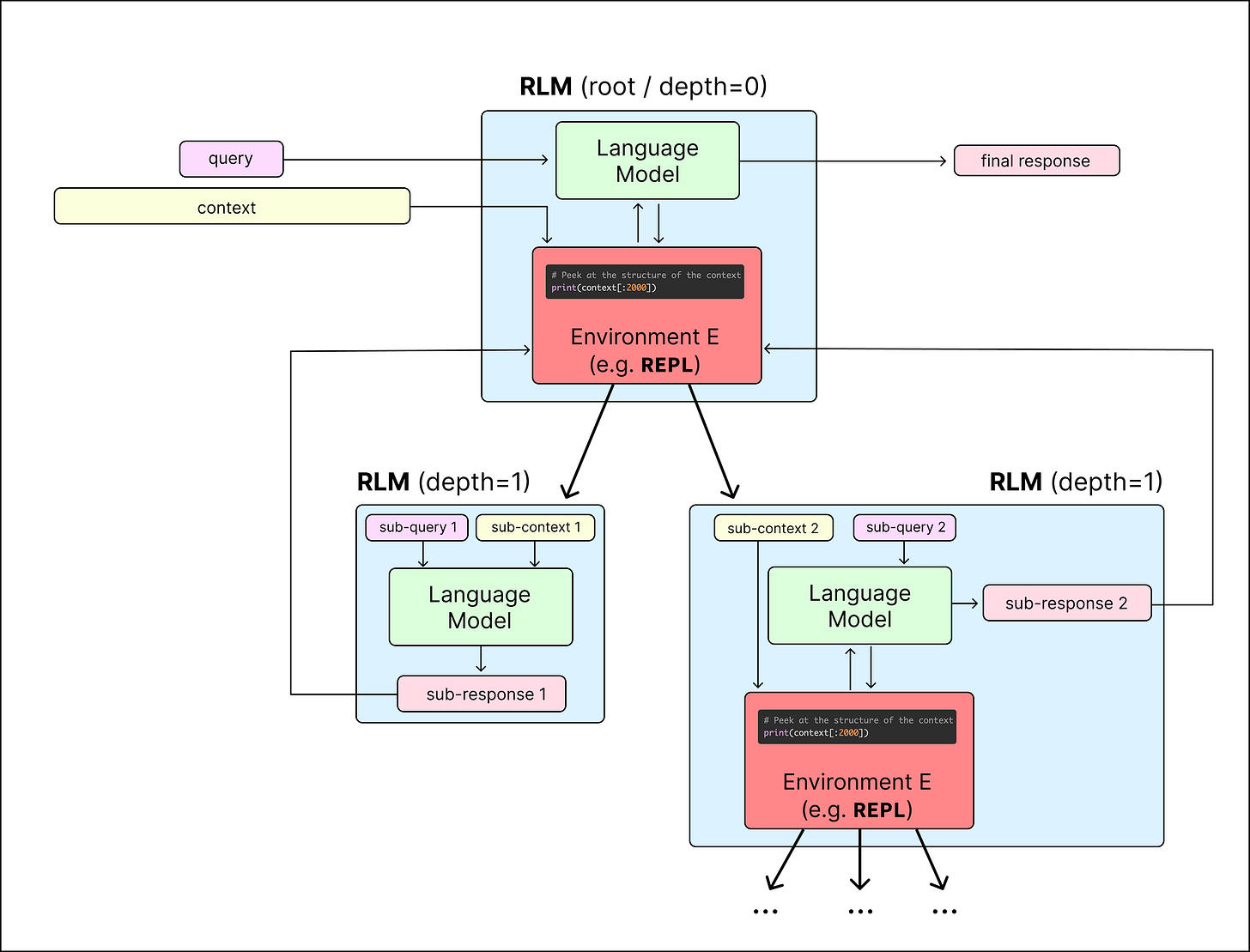

The recursive part: the model can spawn sub-agents (copies of itself with the same architecture) to process specific slices. Each sub-agent gets a manageable chunk, reasons over it within its own context window, and returns a result to the parent. The parent model’s context is never polluted with irrelevant information from chunks it didn’t need to see.

Concretely, the system has three components:

A context variable holding the document (potentially 10M+ tokens)

An rlm_agent(query, context) function that delegates to child agents with identical architecture

Standard Python libraries (json, re, numpy) pre-loaded in the REPL

The agent writes code, executes it, observes results, and iterates. It’s not tool use in the traditional sense. The model lives inside a programming environment, writing and executing code as its primary mode of “reasoning.”

But Isn’t This Just...

The online discourse has predictably asked: “Isn’t this just RAG? Isn’t this just a coding agent? Isn’t this grep with extra steps?”

The distinction matters, and it’s architectural:

RLM vs. RAG: In RAG, retrieved chunks get injected into the prompt. The model reads them directly. In an RLM, the document stays inside the REPL. The model writes code to extract only what it needs, and only those extracted results enter the context. The document is never read wholesale.

RLM vs. Standard coding agents: Both combine LMs with code execution. But in typical agent frameworks, the model calls sub-agents as independent tools. The REPL and the sub-agent are separate. In an RLM, the sub-agent is a function inside the REPL. The parent writes an algorithm, calls rlm_agent() as part of that algorithm, and the results flow back into the program’s execution.

RLM vs. Simple grep: Grep is one operation that an RLM might write. But the power is in composition, where the model can write arbitrary programs that combine search, filtering, aggregation, and recursive delegation.

As co-author Alex Zhang puts it: “It’s not the sub-agent having access to a grepper that matters; it’s that the sub-agent is called from and communicates inside of the REPL.”

What the Model Actually Does

One of the most interesting details from Zhang’s blog and the paper is that the authors didn’t hand-design decomposition strategies. They gave the model a REPL with a recursive call function and observed what emerged. The model independently discovered several interesting strategies:

Peeking: examining the first few thousand characters to understand document structure before doing anything else

Grepping: writing a regex to narrow down relevant lines from massive contexts

Partition + Map: chunking the context into pieces and recursively processing each one

Programmatic processing: for structured tasks like tracking git diffs, the model would write a complete program to solve the task in one shot rather than reasoning about it line by line

This matters because the decomposition strategy is not prescribed. The model figures out how to interact with its context at inference time. The authors make a useful distinction here. Most agent frameworks do task decomposition (breaking a complex problem into simpler sub-problems), while RLMs additionally do context decomposition (breaking a large input into manageable pieces).

Standard agents decide what to do. RLMs also decide what to look at.

It’s also worth noting that all published results use only a recursive depth of 1. The root model can call sub-agents, but those sub-agents don’t call further sub-agents. The architecture supports deeper recursion, but it hasn’t been tested yet. The current reported results represent the shallow end of what this system can do.

The Results

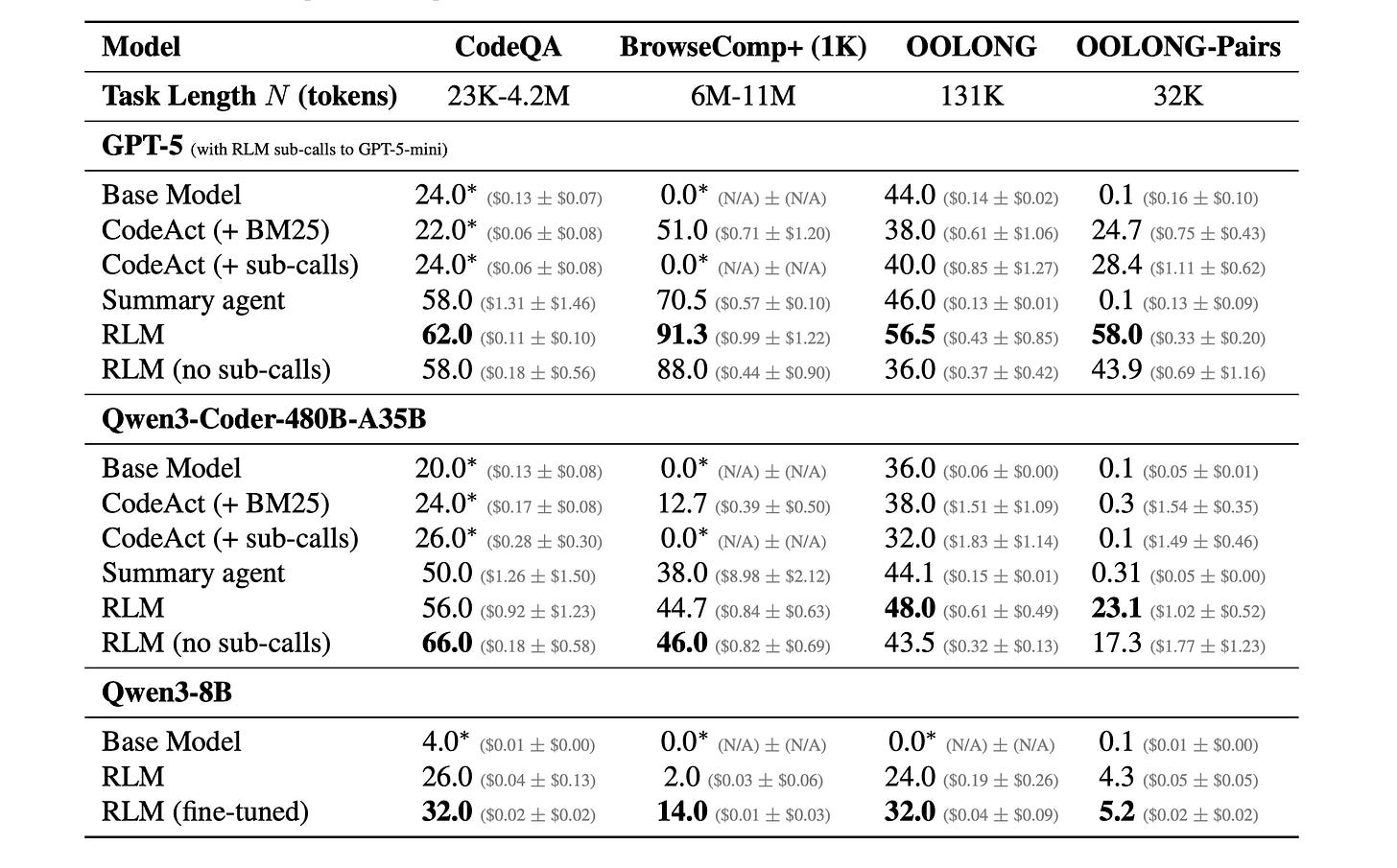

The paper evaluates RLMs on several benchmarks, but two results stand out.

OOLONG-Pairs requires models to identify relationships across scattered statements in long documents. This is a quadratic reasoning task that requires connecting information from many different locations, not just finding a single needle.

RLM(GPT-5) achieved a 58.0 F1 score on a task where the same model without the recursive scaffold couldn’t get past 0.1. That’s not an incremental improvement. It’s the difference between complete failure and meaningful capability on a class of problems that current architectures cannot handle at all.

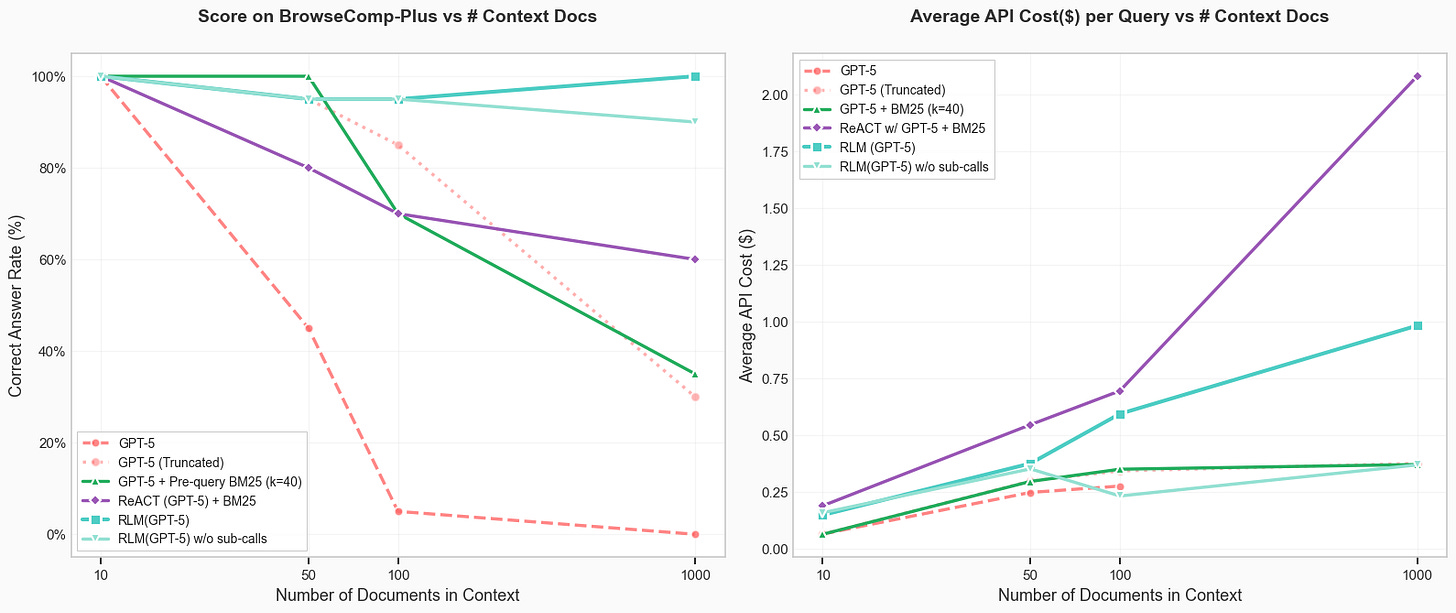

BrowseComp-Plus requires multi-hop reasoning across large collections of documents, synthesizing information scattered across up to 1,000 sources. At the 1,000-document scale, vanilla frontier models completely failed (0.0%, hitting context limits). RLM(GPT-5) led with 91.3% accuracy, well ahead of the next best baseline (Summary agent at 70.5%) and CodeAct + BM25 at 51.0%.

On broader long-context tasks:

RLMs process inputs up to two orders of magnitude beyond the base model’s context window

RLM-Qwen3-8B (a post-trained 8B model) outperforms the base Qwen3-8B by 28.3% on average

That same 8B model approaches GPT-5 quality on three long-context benchmarks

That last point deserves emphasis: you can take a small open model, teach it to manage its own context recursively with minimal post-training, and get competitive with a frontier model on tasks where raw context window size usually dominates.

Current Limitations (Worth Being Honest About)

RLMs are early-stage, and the authors are transparent about what doesn’t work yet.

The constraints fall into two categories:

The model has to be a good coder. This is the most fundamental constraint. RLMs offload reasoning into code, which means the underlying model needs strong programming ability. Weaker models struggle to write effective REPL programs, and models with long internal reasoning traces sometimes burn through their output budget on “thinking” before producing any executable code at all. This creates a floor on model capability that doesn’t exist for standard prompting.

Generalization is still fragile. The recursive strategy doesn’t transfer cleanly across model families. Prompts tuned for one model can behave unpredictably on another. The paper reports cases where a model attempted to spawn thousands of simultaneous sub-agents, requiring manual intervention. The inference pipeline also currently runs sub-agents sequentially (blocking), which means deep recursion gets slow. Parallelizing sub-agent calls is an obvious engineering improvement, but it isn’t implemented yet.

These are real constraints for anyone thinking about deploying RLMs today.

What Makes This Interesting for the Future

RLMs point toward something broader than a clever inference trick.

There are a few threads worth pulling on:

Context management as a learnable skill. The dominant approach to long-context has been architectural: bigger windows, better position encodings, and more efficient attention. RLMs reframe the problem entirely, where context management isn’t a hardware constraint to engineer around, it’s a capability the model can learn. Instead of asking “how do we fit more tokens in?” the question becomes “can we train models to be selective about what they attend to?” The post-training results on Qwen3-8B suggest the answer is yes.

Native recursive training. The paper shows you can post-train an existing model to be “natively recursive.” The name “recursive LM” comes from this property, where you train a single LM with a fixed context window, and it learns to recursively call itself. The training signal is to solve this task using your REPL and sub-agent calls and avoid doing what most coding agents do today which is try to absorb everything at once.

Zhang’s blog makes a further argument worth watching. The trajectory in which a model chooses to interact with and decompose its context is entirely learnable and could be optimized with RL. If that pans out, it can result in training models that develop better decomposition strategies over time.

Task-agnostic neurosymbolic reasoning. RLMs are not limited to coding tasks. Zhang explicitly argues we should think beyond coding agents. Code could be seen as the medium for general-purpose reasoning.

This idea is converging from multiple directions. Arvind Narayanan independently argued that coding agents succeed precisely because they are a form of neurosymbolic AI. He also observes that complex agentic tasks already involve LLMs writing code that invokes other LLMs, and in principle, you can have arbitrary recursion depth between statistical and symbolic systems. That observation aligns well with the RLM architecture.

When you think about it, the REPL doesn’t strictly need to be a Python environment. It could be a SQL console for database reasoning, a search engine with a scripting layer for research tasks, or a spreadsheet runtime for financial analysis. The underlying pattern stays the same. Give the model a structured environment where it can write instructions, observe results, and recurse.

Convergence prediction. Zhang predicts most future agentic scaffolds will converge toward RLM-like properties. Practitioners are already discovering this empirically through structured context management, transcript storage with grep, and smart compaction, all of which are informal approximations of what RLMs formalize.

Final Words and Resources

For years, the scaling story for long-context LLMs has been to make the context window bigger, hope attention holds up, and just keep throwing more compute at the problem. RLMs suggest something more elegant. The right unit of scaling isn’t the context window itself, but the model’s ability to decide what belongs in it.

What stands out most about RLMs is the efficiency story. An 8B model, given the ability to write programs instead of reading documents, starts competing with models orders of magnitude larger. That kind of gain from a scaffold change alone says something about where the field might be headed.

The authors and other folks have released a few interesting resources worth looking at:

Official codebase: https://github.com/alexzhang13/rlm

Minimal RLM engine: https://github.com/alexzhang13/rlm-minimal

ADK integration: https://github.com/LiamConnell/adk-python/tree/66a757f5/contributing/samples/rlm

More on RLMs: https://discuss.google.dev/t/recursive-language-models-in-adk/323523

Blog post: https://alexzhang13.github.io/blog/2025/rlm/

Full paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.24601

I have a project where my claude. Md first instruction is “whenever you find new critical information insert in the md itself”. Overtime it built a mental map of the entire AWS deployment architecture and devops work is a breeze nowadays with it.